Crédits

Web documentaire réalisé à l’occasion de l’exposition « Le Monde enchanté de Jacques Demy » conçue et présentée par la Cinémathèque française – Musée du cinéma, en partenariat avec Ciné-Tamaris, à Paris du 10 avril au 4 août 2013.

- Direction éditoriale

- Cécile Dubost

- Coordination du projet et sélection iconographique

- Bertrand Keraël

- Textes

- Gaël Lépingle

- Voix française

- Grégoire Leprince-Ringuet

(Enregistré au studio Scopitone, Paris) - Voix anglaise

- David Gasman

- Prises de vue, prise de son, montage et extraits

- Cécile Dubost, Olivier Gonord, Bertrand Keraël, Frédéric Rousselot, Fred Savioz

- Prises de vues de la « peau d’âne »

- Stéphane Dabrowski

- Traduction anglaise

- John Tyler Tuttle

- Gestion des droits

- Catherine Hulin, Aurélia Thyreau

- Conception et réalisation

- WAMI Concept et La Blogothèque

- Direction artistique et graphisme

- Simon Dupont-Gellert et Clémence Brunet

- La Cinémathèque remercie tout particulièrement

- Rosalie Varda, Agnès Varda, Mathieu Demy, Fanny Lautissier (Ciné-Tamaris), Agostino Pace, Hector Pascual, Sylvie Richard et Bernadette Gazzola-Dirrix (INA), Nathalie Chevalier (Atelier MBV), Prunelle Blanc.

- Ainsi que pour leur aimable concours

- Béatrice Abonyi, Alban Agnoux, Nathalie Bourgeois, Charlyne Carrère, Xavier Jamet, Ghislaine Lassiaz, Matthieu Orléan, Sylvie Vallon, ainsi que l’ensemble des équipes de la Cinémathèque française qui ont participé à la réalisation de ce projet.

- Page d’accueil

- Les Demoiselles de Rochefort – Tournage

Hélène Jeanbrau © 1996 Ciné-Tamaris - Jacques Demy et le Merveilleux

- Château-Bougon : interview Jacques Demy, 23 décembre 1970

© INA - Il était une fois

- Jacquot de Nantes, Agnès Varda, 1990

© 1990 Ciné-Tamaris

Le Pont de Mauves, Jacques Demy, 1944 - Film

© Succession Demy

Attaque nocturne, Jacques Demy, 1948 - Film

© Succession Demy

Jacquot de Nantes d’Agnès Varda, 1990 - Extrait

© 1990 Ciné Tamaris

Les Demoiselles de Rochefort, Jacques Demy, 1966 - Extrait

© 1996 Ciné Tamaris - Il faut croire à ses rêves

- Peau d’Âne, Jacques Demy, 1970

Michel Lavoix © 2003 Succession Demy

Lola, Jacques Demy, 1960

© Agnès Varda

Les Parapluies de Cherbourg, Jacques Demy, 1963

Leo Weisse © 1993 Ciné-Tamaris - Ne s’étonner de rien

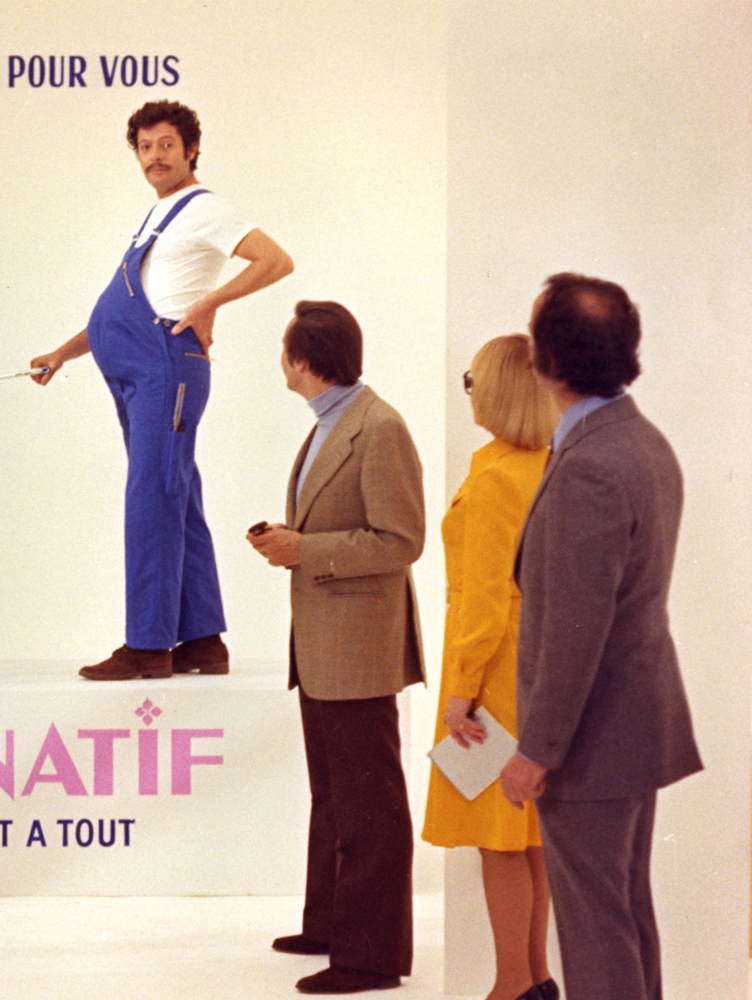

- L’Événement le plus important depuis que l’homme a marché sur la Lune, Jacques Demy, 1973

Michel Lavoix © 1996 Ciné-Tamaris

L’Événement le plus important depuis que l’homme a marché sur la Lune, Jacques Demy, 1973

Michel Lavoix © 1996 Ciné-Tamaris, coll. Cinémathèque française

L’Événement le plus important depuis que l’homme a marché sur la Lune, Jacques Demy, 1973

© 1996 Ciné Tamaris - Le chant / Un Merveilleux « banal »

- Catherine Deneuve et J Demy : « Peau d’Âne », 2 janvier 1971

© INA

Les Demoiselles de Rochefort, Jacques Demy, 1966 - Extrait

© 1996 Ciné Tamaris

Les Parapluies de Cherbourg, Jacques Demy, 1963 - Extrait

© 1993 Ciné Tamaris

[+] Peau d’Âne, Jacques Demy, 1970 - Extrait

© 2003 Succession Demy - Passages

- Une Chambre en ville, Jacques Demy, 1982 - Tournage

© Jean-Pierre Berthomé

Les Demoiselles de Rochefort, Jacques Demy, 1966 (x2)

Hélène Jeanbrau © 1996 Ciné-Tamaris

Les Demoiselles de Rochefort, Jacques Demy, 1966 - Tournage

Hélène Jeanbrau © 1996 Ciné-Tamaris, coll. Cinémathèque française

Parking, Jacques Demy, 1985 - Extrait

© 2012 Ciné Tamaris - Menaces

- Une chambre en ville, Jacques Demy, 1982

Moune Jamet © 2008 Ciné-Tamaris

Les Parapluies de Cherbourg, Jacques Demy, 1963

Leo Weisse © 1993 Ciné-Tamaris

Le Joueur de flûte, Jacques Demy, 1971

Michael Joseph © 1971-Sagittarius Productions Inc.

Les Parapluies de Cherbourg, Jacques Demy, 1963

Leo Weisse © 1993 Ciné-Tamaris - Travestissements

- Les Demoiselles de Rochefort, Jacques Demy, 1966

Hélène Jeanbrau © 1996 Ciné-Tamaris

Lola, Jacques Demy, 1960

© Agnès Varda

Peau d’Âne, Jacques Demy, 1970 (x2)

Michel Lavoix © 2003 Succession Demy

La Baie des anges, Jacques Demy, 1962

© Agnès Varda

Lady Oscar, Jacques Demy, 1978

Michèle Laurent-Bouder © 1979-Filmlink International - Le noir sous le rose

- Une chambre en ville, Jacques Demy, 1982

Moune Jamet © 2008 Ciné-Tamaris

Jeune public- Il était une fois un conte

- Peau d’Âne - Six plaques de verre de type Lapierre [sd]

Peau d’Âne - Douze plaques de verre de type Lapierre [sd] - Chercher l’erreur

- Peau d’Âne, Jacques Demy, 1970 (x4)

Michel Lavoix © 2003 Succession Demy - Le cinéma, c’est de la Magie

- Jacquot de Nantes d’Agnès Varda, 1990 - Extrait

© 1990 Ciné Tamaris

Attaque nocturne, Jacques Demy, 1948 - Film

© Succession Demy

Peau d’Âne, Jacques Demy, 1970 - Extrait

© 2003 Succession Demy

Crédits

Sauf mention contraire, les images proviennent de Ciné-Tamaris.

Contact us

References

- Fiche biographique de Jacques Demy

- Jacques Demy dans les collections de la Cinémathèque française

Jacques Demy à l’INA - Contenu du webdocumentaire

-

Webdocumentaire au format pdf : Français English

Jacques Demy et le Merveilleux au format mp3 : Français English

Peau d'Âne et le Merveilleux au format mp3 : Français English - Le Monde enchanté de Jacques Demy

- Matthieu Orléan, Alban Agnoux, Rosalie Varda-Demy

Skira-Flammarion, 2013 - Jacques Demy

- Olivier Père, Marie Colmant

La Martinière, 2010 - Chansons et textes chantés

- Jacques Demy

Léo Scheer, 2004 - Cahier de notes sur…Peau d’Âne de Jacques Demy

- Alain Philippon

Les Enfants de cinéma, 2001 - Les Demoiselles de Rochefort

- Michel Marie

Les Enfants de cinéma, [sd] - Le cinéma enchanté de Jacques Demy

- Camille Taboulay

Cahiers du cinéma, 1996 - Les Parapluies de Cherbourg, étude critique

- Jean-Pierre Berthomé

Nathan, 1995 - Jacques Demy et les racines du rêve

- Jean-Pierre Berthomé

L’Atalante, 1996 - Les Demoiselles de Rochefort (texte du film)

- Jacques Demy

Solar, 1967

« My life is a long childhood », sang the young women of Rochefort in a working version of their famous song. This is also what Jacques Demy thought about his own life. His wonderment before the puppet shows to which his mother took him led to the vocation, at a very young age, of cinema seen as a dream or magical toy… For the little « Jacquot of Nantes », everything started from childhood and all his art contributed to prolonging it. In the family attic, fitted out as a « studio », he painted stories on strips of celluloid, also shooting frame by frame with an amateur movie camera to animate his cardboard characters. Alone and like a craftsman, he invented worlds for himself, small-scale models of the fantasies to come.

Demy liked to bring back his characters from one film to the next, thus dreaming of a truly marvellous world ruled by his own laws. Thus Lola/Anouk Aimée, abandoned in the film bearing her name, would reappear in Model Shop; Roland Cassard/Marc Michel also evokes Lola in The Umbrellas of Cherbourg: « In the past, I loved a woman. She didn't love me. She was called Lola. » And although scheduling conflicts prevented Nino Castelnuovo (Guy in Umbrellas…) from playing Bill, the fairground worker in The Young Girls of Rochefort, that had been the intention at the outset. Demy often had to abandon continuities of fate, even though allusions persist, like a memory or the trace of the idea: again in Model Shop, Lola relates how her lover left her for a woman who gambled: the Jackie from… Bay of Angels…

Once he had grown up, Demy would like the sequence-length shot whose duration helped in creating a seamless world… He would imagine bringing back characters and actors from film to film, thus dreaming his oeuvre like a village and a world, a great uninterrupted fiction, constantly run through with influences and returns. He would shoot in the street, but as a painter of reality, would also intervene on the motif: the large flats of colours on the façades of the houses in Rochefort, the macadam smoothed expressly for Gene Kelly's dance… The Marvellous, from the Latin mirabilia (« astonishing, admirable things »), meets an intimate need to transfigure reality: doubtless to protect himself from it and to substitute a desirable world for it.

« A real fairytale! » exclaims one of the characters in Lola. And why not? Anything can always happen: it suffices to believe in one's luck, in the magical power of music, fairies, and love. Like Lola, precisely, who, like a Sleeping Beauty, awaits the return of her Prince Charming. Like Delphine in Young Girls who believes in the predestination of individuals and hopes for an amorous encounter in the streets of Rochefort, and that all will end well. Or else Donkey Skin who sings: « If a prince charming does not come to take me away, I swear here that I shall go find him myself. »

+

+

It's necessary to believe in luck or fate. Luck or fate? Both, no doubt, as long as the belief persists that love is the encounter of two halves long separated. Thus the painter paints his ideal female love without knowing she lives in Rochefort, and both already sing the same song, the melody of happiness, as if by anticipation. Or it is the Prince and Donkey Skin – played by the same two actors – who know, without knowing each other, the same song (Amour, je t’aime tant), the sign that, to become reality, an encounter awaits only the roll of the dice of fate, the nudge of a fairy... or the magic wand of cinema.

To believe is also not to be amazed by anything: either finding one self in Hell or that a donkey excretes gold like a slot machine. Nor is there anything amazing in the fact that the characters sing to speak. No more so than a man getting « pregnant »; at most his doctor will tell him that « it's not serious, it's disconcerting ».

What is ordinarily extraordinary must not astonish more than it should… In the universe of the Marvellous, everything is justified all the better since one is not obliged to provide too many explanations. And even if the entourage sometimes remains incredulous or critical…

Not being amazed… It happens that people speak in alexandrines as if it were nothing. And like dancing that comes naturally in walking, singing creates no break. Hollywood musicals made a « number » out of it, a remarkable moment apart. According to Demy, singing integrates more into daily life and customary situations, to the point of becoming the language itself. All the more so in that Michel Legrand's music is close to the rhythm of spoken language and human breathing. Amazing Marvellous that can attain a certain form of realism.

The direction does not oblige on the characters a bare lyricism, as in an empty space, but invents concrete activities for them at the same time. Thus, Geneviève and her mother « discuss » in their umbrella shop whilst one arranges a floral bouquet and the other prepares a meal. Thus Donkey Skin, sometimes as a slattern, sometimes a princess, breaks eggs and prepares the mixture whilst singing the recipe for her love cake.

The Marvellous presupposes a passage, a bridge between two worlds, in the image of the transporter bridge that appears in the titles of A Room in Town and transports the fairground people at the beginning of The Young Girls of Rochefort. Better than an overly prosaic road bridge, the transporter bridge moves its passengers in the air, as if suspended and flying. The fairground people entering Rochefort at the beginning of the film and leaving at the end, mark the intrusion of the Marvellous in the everyday world: they bring songs, dances and colours to a gloomy daily life. The Marvellous is dreamt like an alternative life.

Each time, it is a crossing that allows access to the Marvellous, whether it be multicoloured or bicoloured like the realm of the dead.

Although it creates a protected space apart, the Marvellous does not always shelter from misfortune, and sometimes the return of the so-called « real world » is all the harsher for having been kept at bay: the war in Algeria that separates those who love each other in The Umbrellas of Cherbourg; the insistent presence of the Vietnam War in Model Shop; labour strikes and confrontations in A Room in Town; or the sudden news, on the page of crime stories, of a woman hacked into pieces…

Sometimes that is due to a cloud in a blue sky or to a mood so that the dream becomes tarnished and the fête veers to masquerade. It is Geneviève refusing to join in the carnival-time celebrations in the streets of Cherbourg: « I find these people ridiculous. » It is the snow falling at the end of The Umbrellas and covering the lovely décor of a dead love with a shroud. Sad fête.

The threat does not always come from outside, but from the Marvellous itself in which certain characters live (retreat), victims of prefabricated dreams of love, built up to the point of sham: the twin sisters' wigs; the bleached hair of the painter in The Young Girls of Rochefort and Jackie in Bay of Angels; Lola's boasting: « Touch me. I washed my hair - you'd say it was silk. » Marvellous finery or flashy signals? Signs of femininity are exhibited and exacerbated, and from disguise or jewels (the stage costumes of Lola and the young girls, Donkey Skin's weather gown), we go to dressing-up: glitter, heavy eye makeup, feather boa or garish lipstick.

Sometimes the handsome uniform completely sucks out the person's lifeblood: Geneviève's mink, at the end of Umbrellas, imprisons her in her new status as a married, kept woman. Édith will manage to twist the use in A Room in Town, streetwalking naked under her fur coat. And the dead donkey's skin with which the princess covers herself will become a dazzling gown at court.

The threat does not always come from outside, but from the Marvellous itself in which certain characters live (retreat), victims of prefabricated dreams of love, built up to the point of sham: the twin sisters' wigs; the bleached hair of the painter in The Young Girls of Rochefort and Jackie in Bay of Angels; Lola's boasting: « Touch me. I washed my hair - you'd say it was silk. » Marvellous finery or flashy signals? Signs of femininity are exhibited and exacerbated, and from disguise or jewels (the stage costumes of Lola and the young girls, Donkey Skin's weather gown), we go to dressing-up: glitter, heavy eye makeup, feather boa or garish lipstick.

Sometimes the handsome uniform completely sucks out the person's lifeblood: Geneviève's mink, at the end of Umbrellas, imprisons her in her new status as a married, kept woman. Édith will manage to twist the use in A Room in Town, streetwalking naked under her fur coat. And the dead donkey's skin with which the princess covers herself will become a dazzling gown at court.

The threat does not always come from outside, but from the Marvellous itself in which certain characters live (retreat), victims of prefabricated dreams of love, built up to the point of sham: the twin sisters' wigs; the bleached hair of the painter in The Young Girls of Rochefort and Jackie in Bay of Angels; Lola's boasting: « Touch me. I washed my hair - you'd say it was silk. » Marvellous finery or flashy signals? Signs of femininity are exhibited and exacerbated, and from disguise or jewels (the stage costumes of Lola and the young girls, Donkey Skin's weather gown), we go to dressing-up: glitter, heavy eye makeup, feather boa or garish lipstick.

Sometimes the handsome uniform completely sucks out the person's lifeblood: Geneviève's mink, at the end of Umbrellas, imprisons her in her new status as a married, kept woman. Édith will manage to twist the use in A Room in Town, streetwalking naked under her fur coat. And the dead donkey's skin with which the princess covers herself will become a dazzling gown at court.

Black behind pink

The earliest versions of the scripts written by Demy are striking for their blackness, progressively watered down or concealed by successive rewritings. One of the very first versions of The Young Girls of Rochefort imagined the painter crushed by the fairground people's lorry. The kingdom of Donkey Skin was to have been inhabited by hanged men, skeletons and wandering plague victims. And Guy was supposed to have returned in Young Girls, having closed his garage following the death of his wife.

The earliest versions of the songs are also cruder. That of the painter in Young Girls gushed with exuberant sensuality: « The angels of the night, magic spells of the dream / Crowned with sun will flood her breasts / From her mouth blood will burst her lips / Where fleshy desire will spring forth by night. » And Donkey Skin: « Will you wait for me to be dead / Having lived the current climate », referring to Geneviève's highly moving confession in Umbrellas: « I who would have died for him, why am I not dead? »

A Room in Town assumes blackness and exhibits it: a violent death, two suicides, garish, dirty colours… The film's whole aesthetic turns upside down the Marvellous, often so colourful in Demy's films, to speak the obligatory blackness without a mask - as in Grimm's fairytales that are, granted, often naive and pleasant but also threatening to produce a lasting effect on the child who will become a spectator.