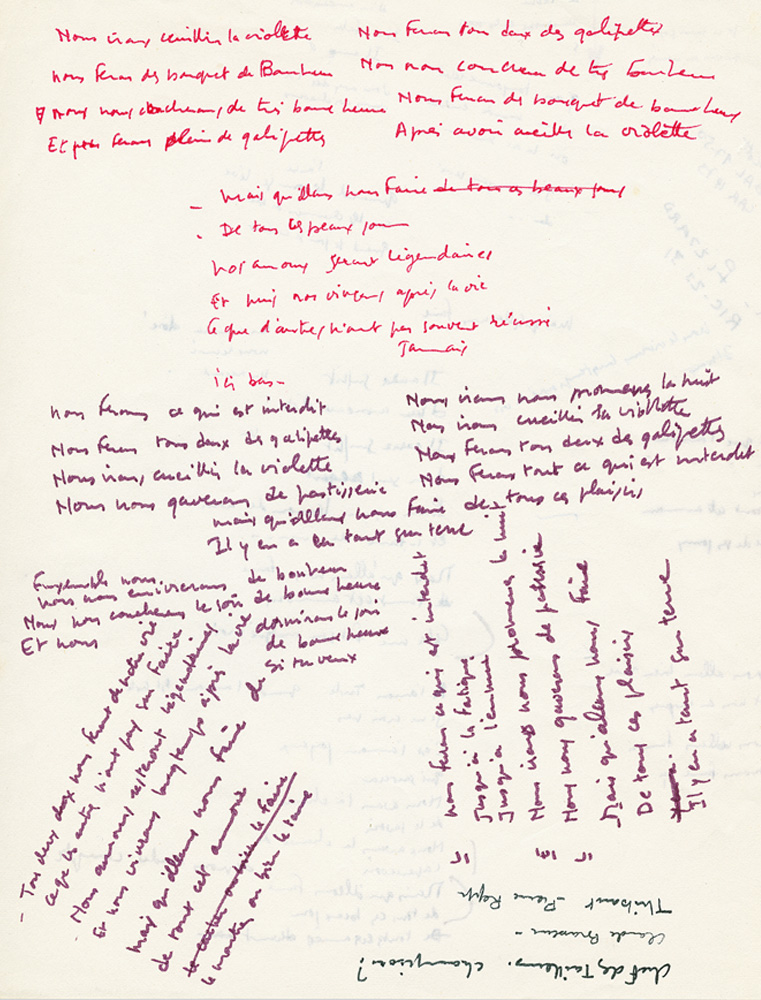

Crédits

Web documentaire réalisé à l’occasion de l’exposition « Le Monde enchanté de Jacques Demy » conçue et présentée par la Cinémathèque française – Musée du cinéma, en partenariat avec Ciné-Tamaris, à Paris du 10 avril au 4 août 2013.

- Direction éditoriale

- Cécile Dubost

- Coordination du projet et sélection iconographique

- Bertrand Keraël

- Textes

- Gaël Lépingle

- Voix française

- Grégoire Leprince-Ringuet

(Enregistré au studio Scopitone, Paris) - Voix anglaise

- David Gasman

- Prises de vue, prise de son, montage et extraits

- Cécile Dubost, Olivier Gonord, Bertrand Keraël, Frédéric Rousselot, Fred Savioz

- Prises de vues de la « peau d’âne »

- Stéphane Dabrowski

- Traduction anglaise

- John Tyler Tuttle

- Gestion des droits

- Catherine Hulin, Aurélia Thyreau

- Conception et réalisation

- WAMI Concept et La Blogothèque

- Direction artistique et graphisme

- Simon Dupont-Gellert et Clémence Brunet

- La Cinémathèque remercie tout particulièrement

- Rosalie Varda, Agnès Varda, Mathieu Demy, Fanny Lautissier (Ciné-Tamaris), Agostino Pace, Hector Pascual, Sylvie Richard et Bernadette Gazzola-Dirrix (INA), Nathalie Chevalier (Atelier MBV), Prunelle Blanc.

- Ainsi que pour leur aimable concours

- Béatrice Abonyi, Alban Agnoux, Nathalie Bourgeois, Charlyne Carrère, Xavier Jamet, Ghislaine Lassiaz, Matthieu Orléan, Sylvie Vallon, ainsi que l’ensemble des équipes de la Cinémathèque française qui ont participé à la réalisation de ce projet.

- Peau d’Âne et le Merveilleux

- Catherine Deneuve et J Demy : « Peau d’Âne », 2 janvier 1971

© INA - Dure réalité du Merveilleux

- Film Peau d’Âne, 23 décembre 1970

© INA

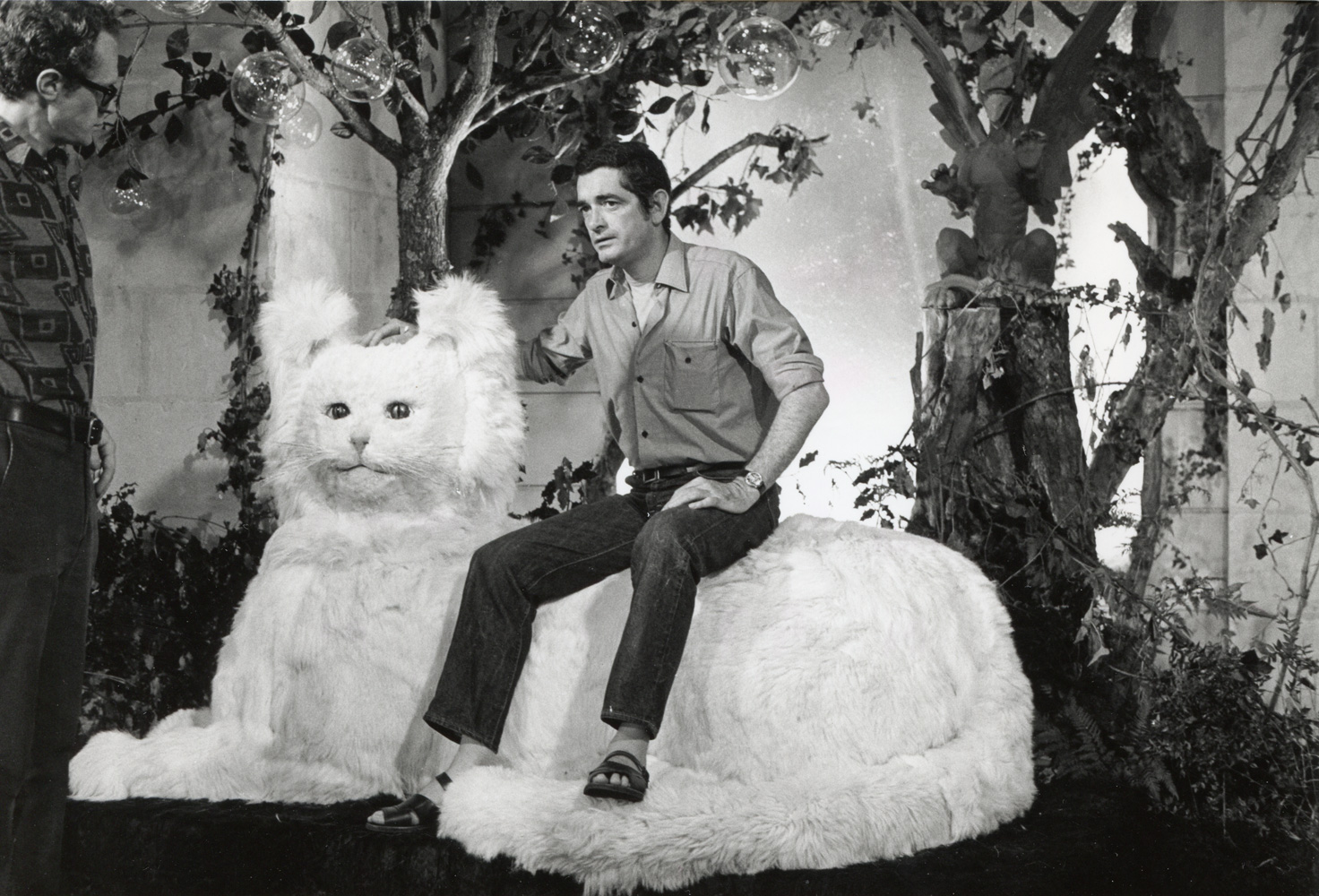

Peau d’Âne, Jacques Demy, 1970 - Tournage

Michel Lavoix © 2003 Succession Demy

Peau d’Âne, Jacques Demy, 1970 - Extrait

© 2003 Succession Demy - Décors

- Peau d’Âne, Jacques Demy, 1970 (x3)

Michel Lavoix © 2003 Succession Demy

Peau d’Âne, Jacques Demy, 1970 (x2)

Michel Lavoix © 2003 Succession Demy, coll. Cinémathèque française

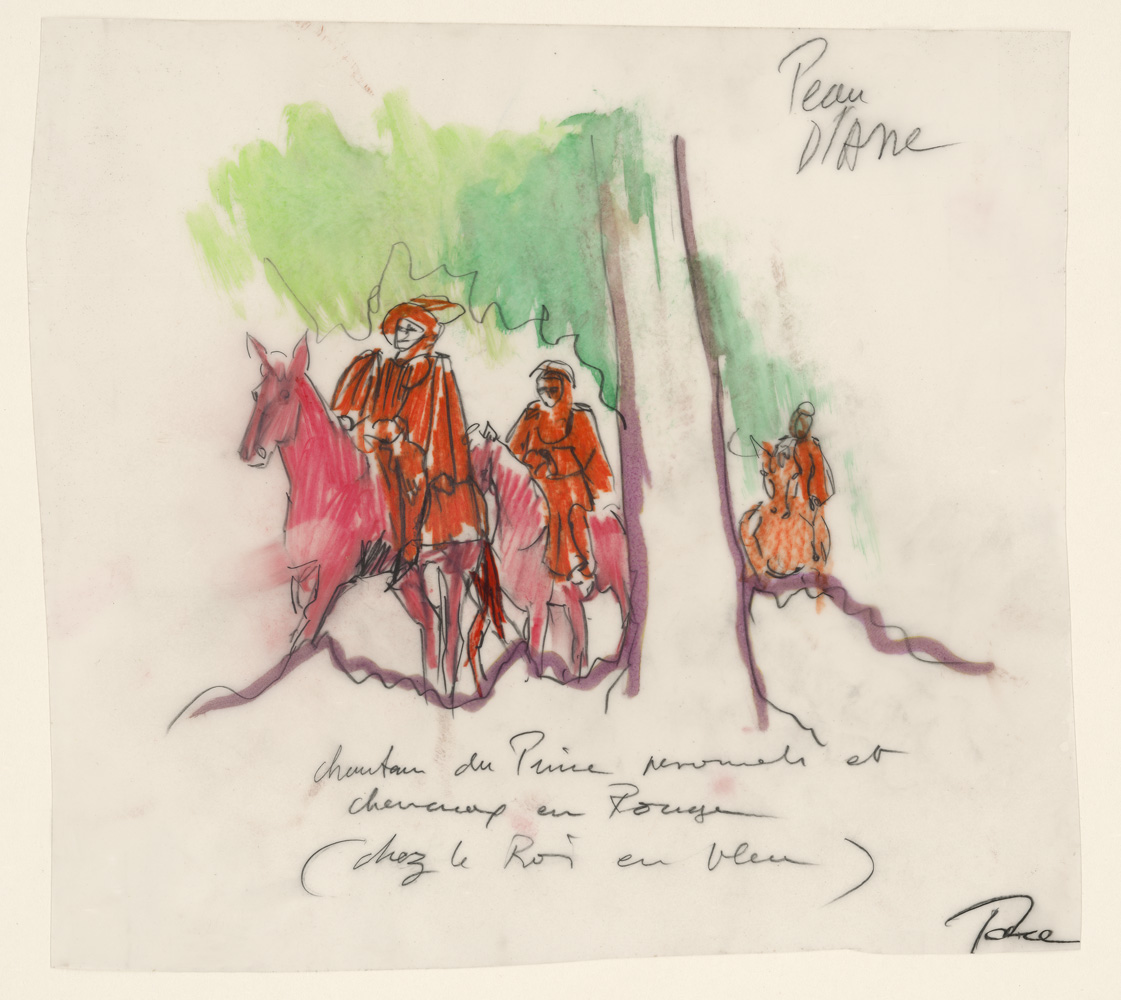

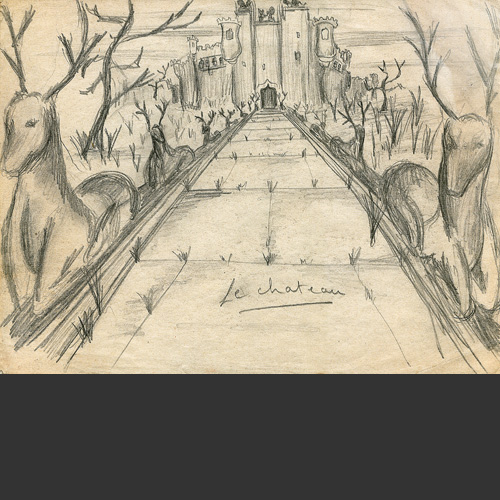

Dessin Jacques Demy

© 2003 Succession Demy

Peau d’Âne, Jacques Demy, 1970 - Extrait

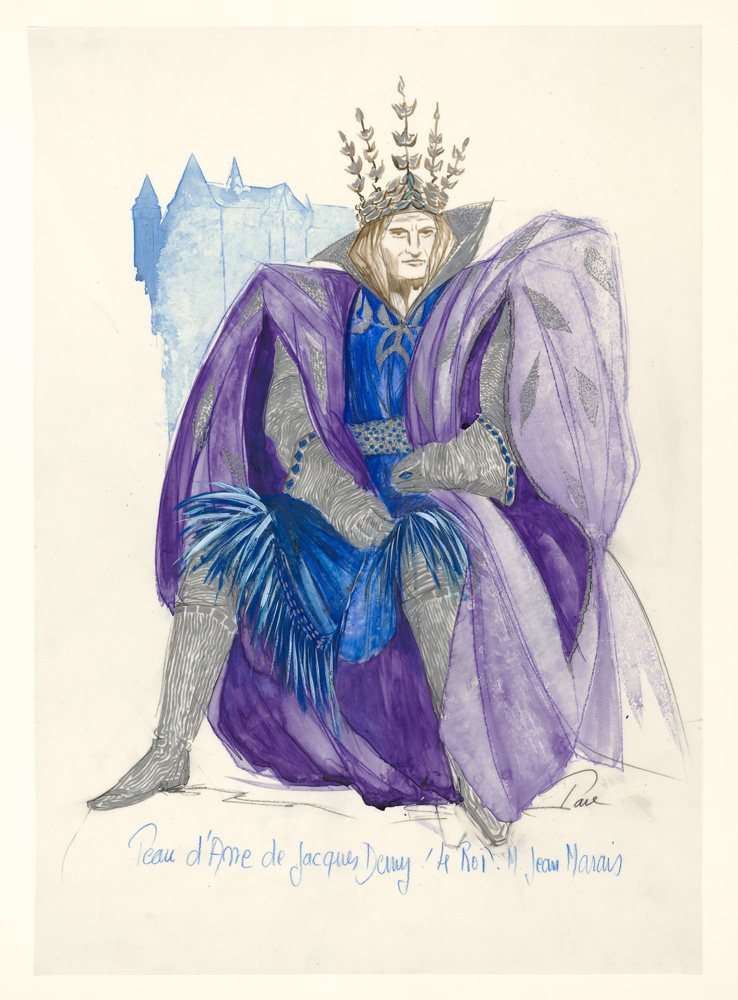

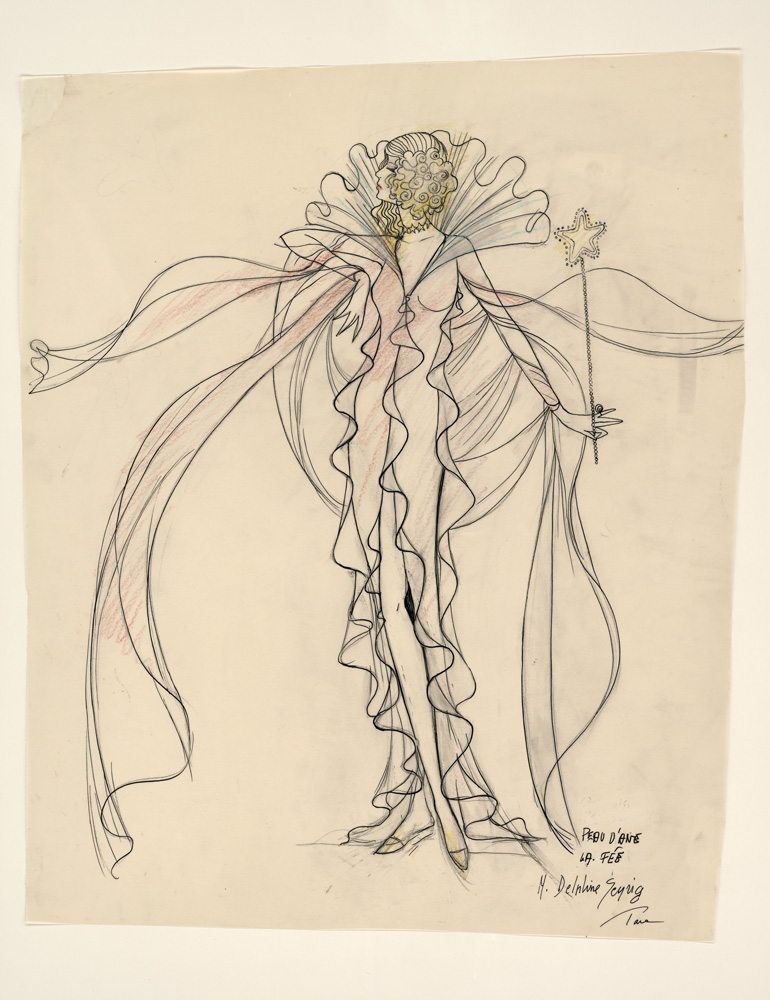

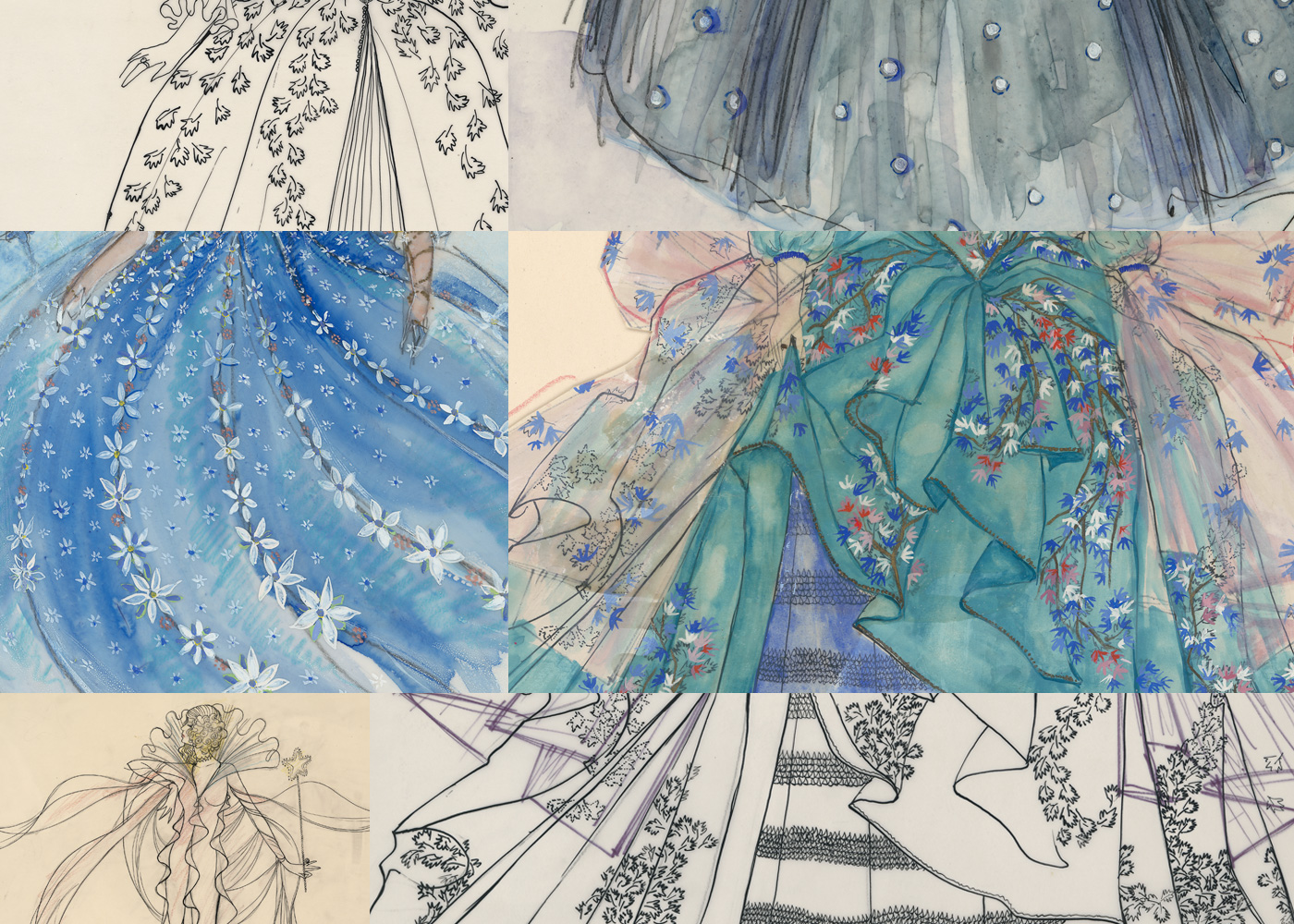

© 2003 Succession Demy - Costumes

- Peau d’Âne, Jacques Demy, 1970 - Maquettes de costume

© Agostino Pace, coll. Cinémathèque française

[+] Peau d’Âne, Jacques Demy, 1970 - Maquettes de costume

© Agostino Pace, coll. Cinémathèque française

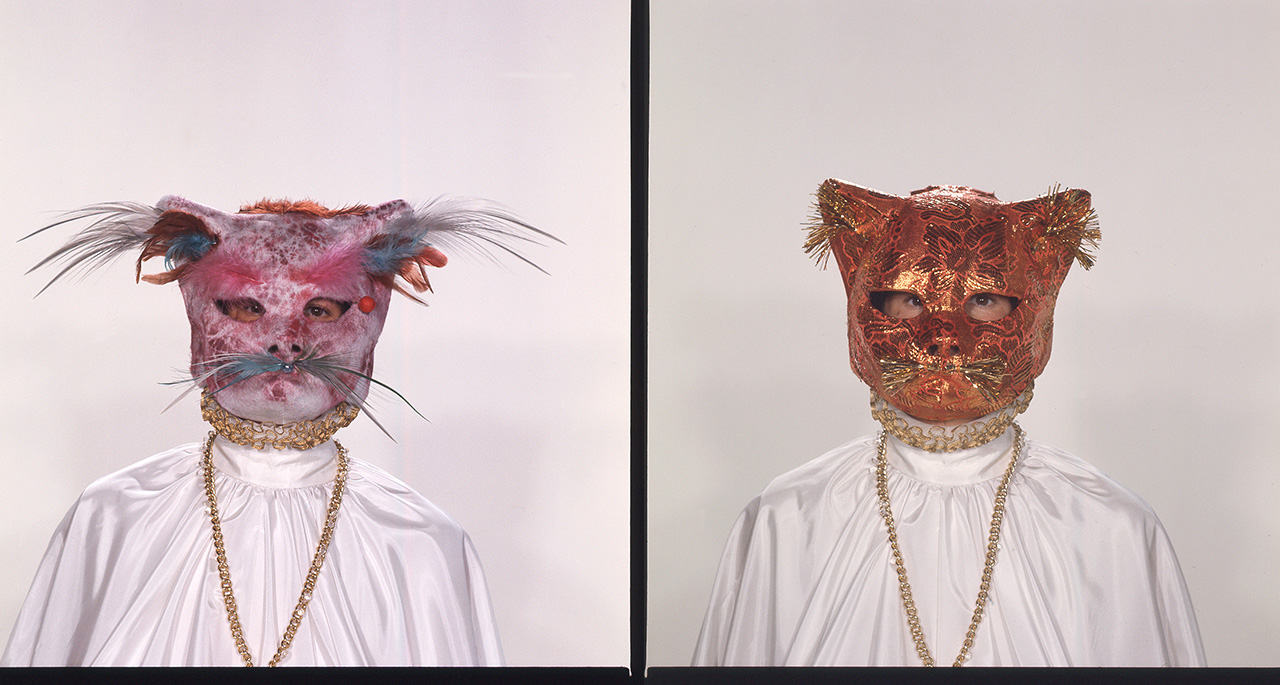

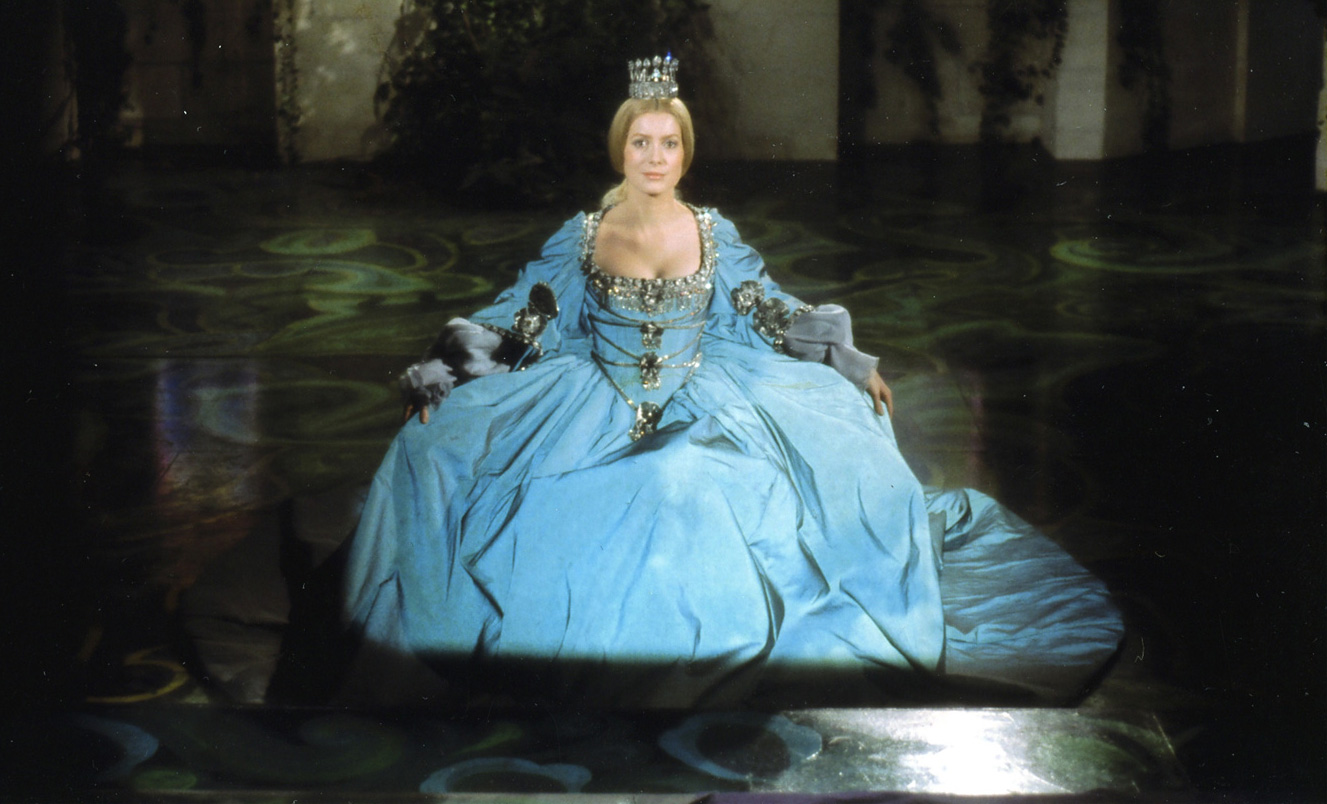

Peau d’Âne, Jacques Demy, 1970 - Ektas

Michel Lavoix © 2003 Succession Demy

[+] Peau d’Âne, Jacques Demy, 1970 - Ektas

Michel Lavoix © 2003 Succession Demy

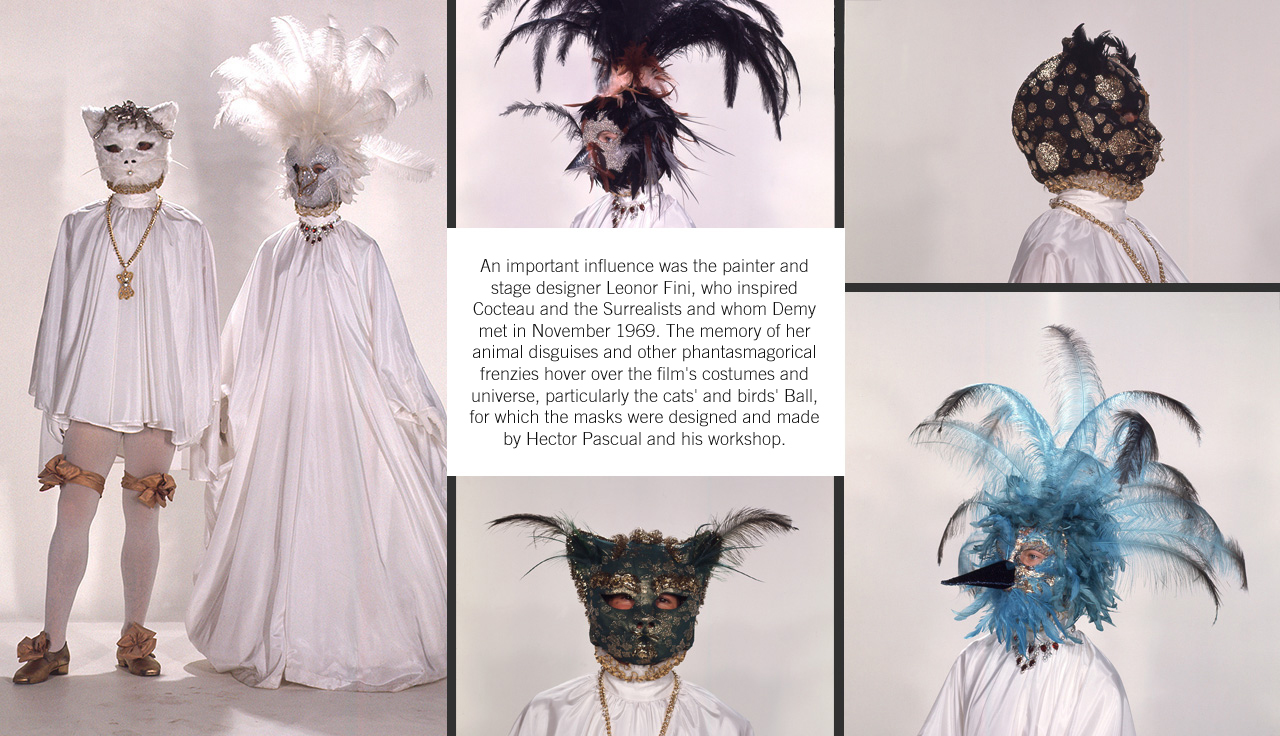

Création des masques : Hector Pascual - Robes

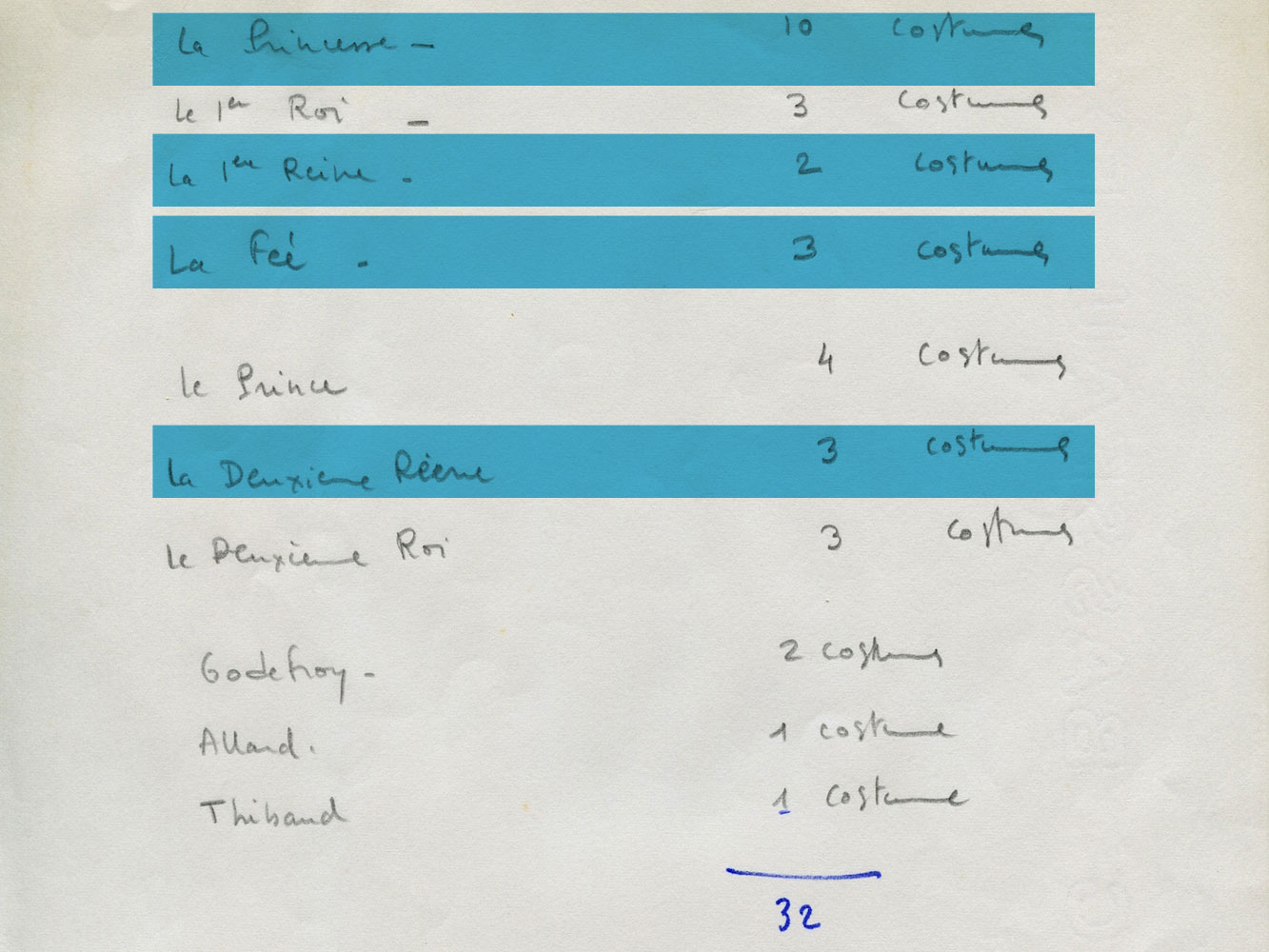

- Note manuscrite de Jacques Demy : liste des costumes

© Ciné-Tamaris

[+] Agostino Pace – Rosalie Varda - Vidéo

Entretien mené par Gaël Lépingle

Réalisation Cécile Dubost, Olivier Gonord

© Cinémathèque française, 2013

Peau d’Âne, Jacques Demy, 1970 - Maquettes de costume (mosaïque)

© Agostino Pace, coll. Cinémathèque française

[+] Catherine Deneuve - Audio

Entretien mené par Serge Toubiana

© Cinémathèque française, 2013

Peau d’Âne, Jacques Demy, 1970 - Ektas

Michel Lavoix © 2003 Succession Demy

[+] Hector Pascual - Audio

Entretien mené par Gaël Lépingle et Bertrand Keraël

Réalisation Cécile Dubost, Bertrand Keraël, Frédéric Rousselot

© Cinémathèque française, 2013

[+] Photographies de la Peau d’âne

© Stéphane Dabrowski, Cinémathèque française

Peau d’Âne, Jacques Demy, 1970 - Ekta

Michel Lavoix © 2003 Succession Demy

[+] Recréer les robes de Peau d’Âne - Vidéo

Agostino Pace – Rosalie Varda – Commentaires : Matthieu Orléan, commissaire de l’exposition « Le Monde enchanté de Jacques Demy »,

Réalisation Olivier Gonord

© Cinémathèque française, 2013

« Recette pour un cake d’amour » (Demy, Legrand)

© Warner Chappell Music France

Peau d’Âne, Jacques Demy, 1970 - Photogramme

© 2003 Succession Demy - Trucages

- Peau d’Âne, Jacques Demy, 1970 - Photogramme

© 2003 Succession Demy

Peau d’Âne, Jacques Demy, 1970 - Extrait

© 2003 Succession Demy

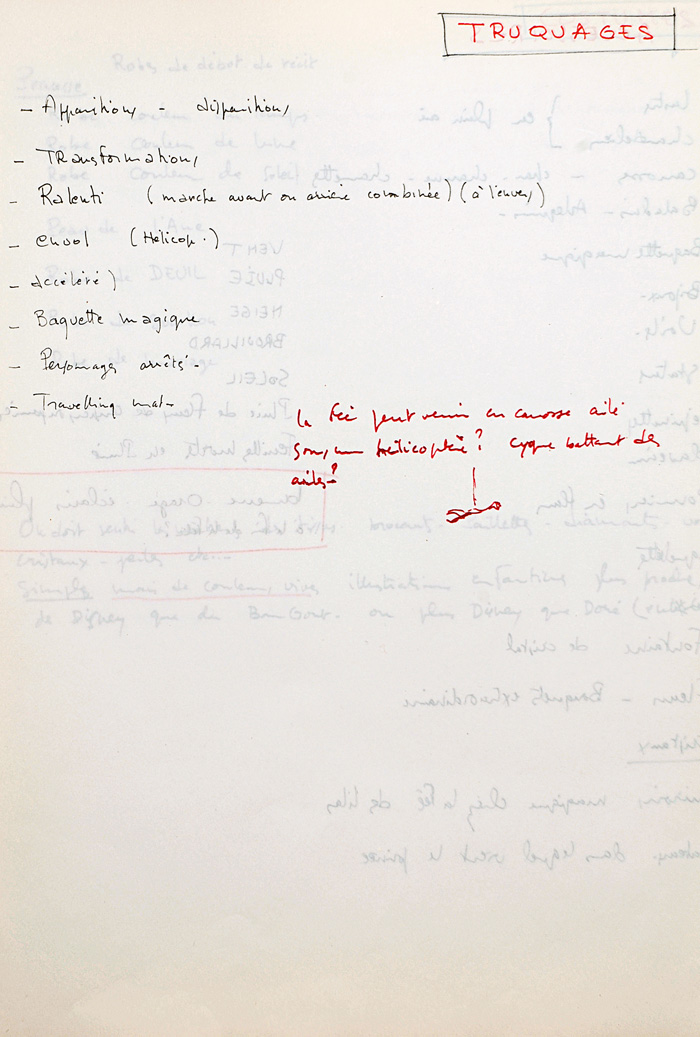

[+] Cahier manuscrit de Jacques Demy : notes sur les trucages

© Ciné-Tamaris - Inspirations

- Illustration de Gutave Fraipont pour Peau d’Âne

Les Contes de Perrault illustrés, Henri Laurens éditeur, 1942

Peau d’Âne, Jacques Demy, 1970 (x 2)

Michel Lavoix © 2003 Succession Demy, Cinémathèque française

Peau d’Âne, Jacques Demy, 1970 - Ekta

Michel Lavoix © 2003 Succession Demy

Tournage Peau d’Âne - commentaires : Agnès et Rosalie Varda - Super 8 couleur

© Ciné-Tamaris - Souvenirs de cinéma, souvenirs d’enfance

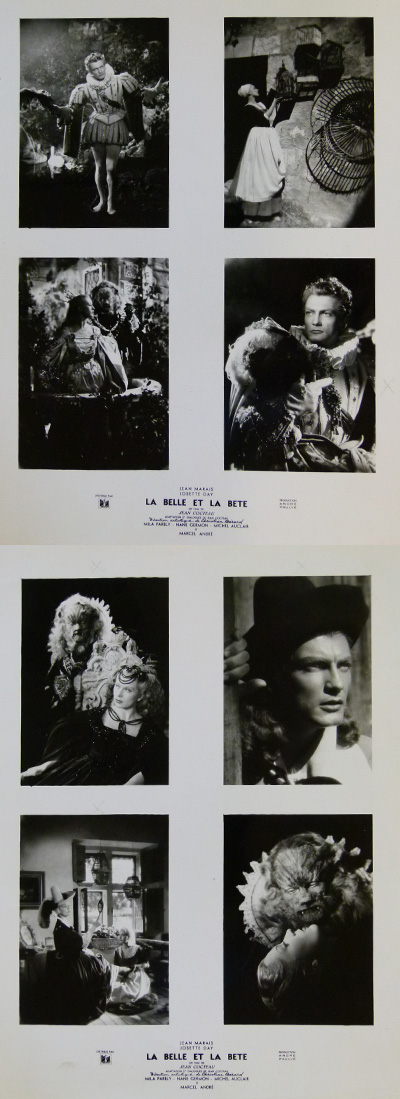

- La Belle et la Bête, Jean Cocteau, 1945 (x 5)

GR Aldo © DR, coll. Cinémathèque française

[+] Pour le cinéma, 19 juillet 1970

© INA

Le Sang d’un poète, Jean Cocteau, 1930 – extrait

© Studio canal - Miroir, mon beau miroir…

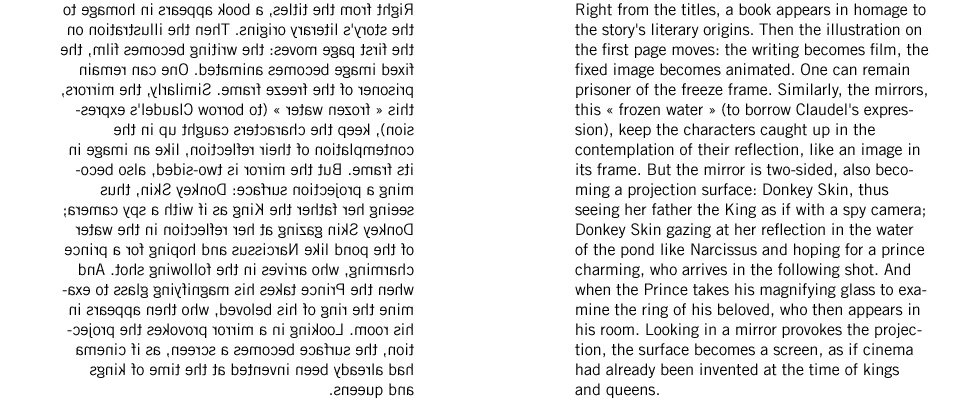

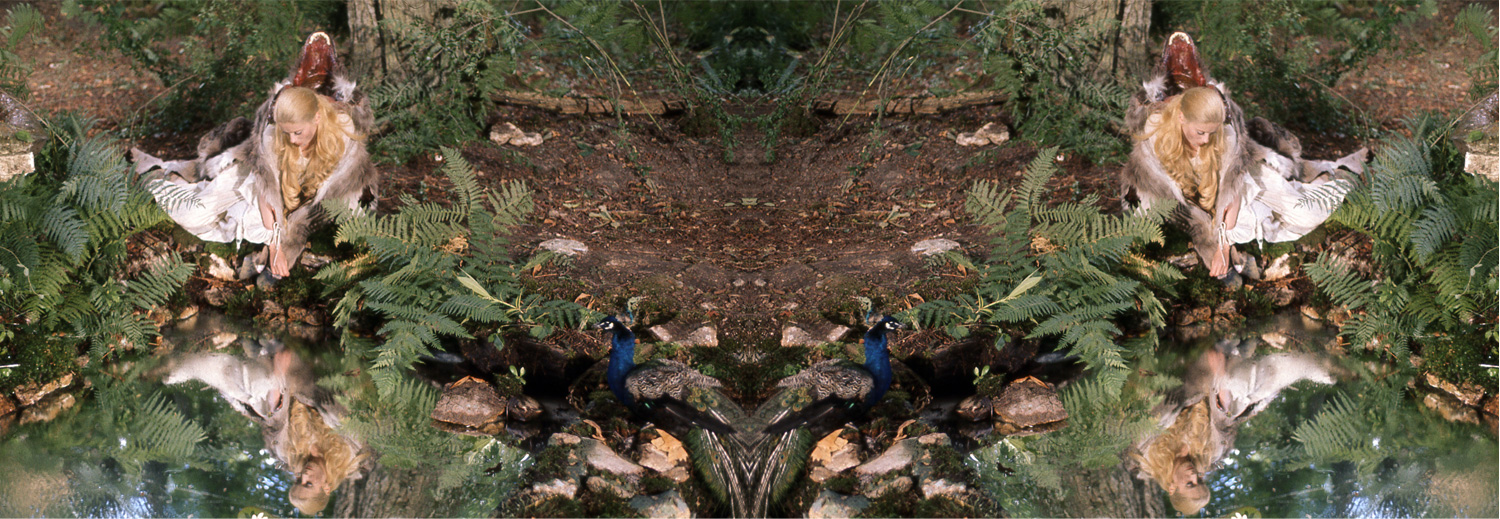

- Peau d’Âne, Jacques Demy, 1970 (x 2)

Michel Lavoix © 2003 Succession Demy

Peau d’Âne, Jacques Demy, 1970 - extrait

© 2003 Succession Demy - La traversée

- Peau d’Âne, Jacques Demy, 1970 - extrait

© 2003 Succession Demy - Le propre et le sale

- Peau d’Âne, Jacques Demy, 1970 - extrait

© 2003 Succession Demy

Peau d’Âne, Jacques Demy, 1970

Michel Lavoix © 2003 Succession Demy

Peau d’Âne, Jacques Demy, 1970

Michel Lavoix © 2003 Succession Demy, coll. Cinémathèque française Peau d’Âne, Jacques Demy, 1970 - extrait

© 2003 Succession Demy - Enfant, où es-tu ?

- [+] Le journal du cinéma, 27 décembre 1970

© INA

Peau d’Âne, Jacques Demy, 1970

Michel Lavoix © 2003 Succession Demy, coll. Cinémathèque française

Peau d’Âne, Jacques Demy, 1970

Michel Lavoix © 2003 Succession Demy

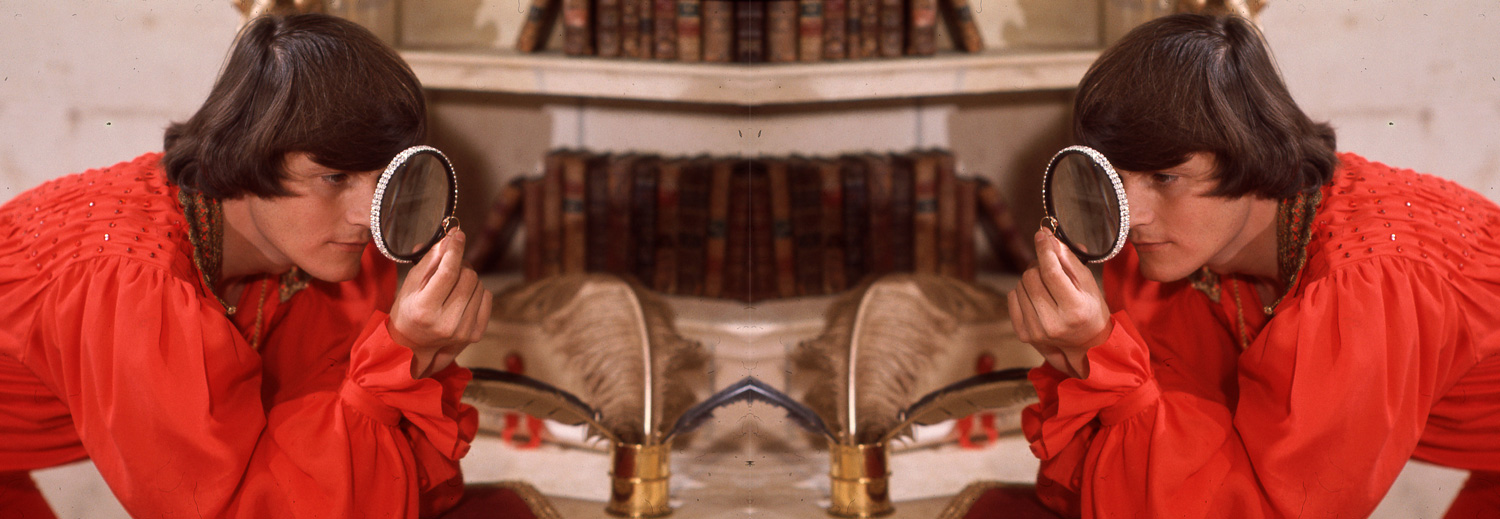

Notes préparatoires de Jacques Demy pour les chansons de Peau d’Âne

© Ciné-Tamaris

Peau d’Âne, Jacques Demy, 1970 - extrait

© 2003 Succession Demy

Jeune public- Il était une fois un conte

- Peau d’Âne - Six plaques de verre de type Lapierre [sd]

Peau d’Âne - Douze plaques de verre de type Lapierre [sd] - Chercher l’erreur

- Peau d’Âne, Jacques Demy, 1970 (x4)

Michel Lavoix © 2003 Succession Demy - Le cinéma, c’est de la Magie

- Jacquot de Nantes d’Agnès Varda, 1990 - Extrait

© 1990 Ciné Tamaris

Attaque nocturne, Jacques Demy, 1948 - Film

© Succession Demy

Peau d’Âne, Jacques Demy, 1970 - Extrait

© 2003 Succession Demy

Contact us

References

- Fiche biographique de Jacques Demy

- Jacques Demy dans les collections de la Cinémathèque française

Jacques Demy à l’INA - Contenu du webdocumentaire

-

Webdocumentaire au format pdf : Français English

Jacques Demy et le Merveilleux au format mp3 : Français English

Peau d'Âne et le Merveilleux au format mp3 : Français English - Le Monde enchanté de Jacques Demy

- Matthieu Orléan, Alban Agnoux, Rosalie Varda-Demy

Skira-Flammarion, 2013 - Jacques Demy

- Olivier Père, Marie Colmant

La Martinière, 2010 - Chansons et textes chantés

- Jacques Demy

Léo Scheer, 2004 - Cahier de notes sur…Peau d’Âne de Jacques Demy

- Alain Philippon

Les Enfants de cinéma, 2001 - Les Demoiselles de Rochefort

- Michel Marie

Les Enfants de cinéma, [sd] - Le cinéma enchanté de Jacques Demy

- Camille Taboulay

Cahiers du cinéma, 1996 - Les Parapluies de Cherbourg, étude critique

- Jean-Pierre Berthomé

Nathan, 1995 - Jacques Demy et les racines du rêve

- Jean-Pierre Berthomé

L’Atalante, 1996 - Les Demoiselles de Rochefort (texte du film)

- Jacques Demy

Solar, 1967

In the middle of the forest, a few unexpected objects contrast sharply with the natural setting and suffice to create a magical world: a mirror, a telephone… Similarly, the great walls of the rooms at Chambord were simply covered with ivy. Ornamentation remains limited to the stained-glass windows and to precise set elements in vast interior spaces: beds, folding screen, thrones, mirror...

Donkey Skin's bed was supposed to be a huge flower opening and closing at bedtime. But when it came time for the shooting, the mechanism did not work. Jacques Demy related: « I had noticed two stags, downstairs, in the entry of Chambord. We had them brought up and made the bed from them, improvising the rest ». In the end, the fake stags, guardians of a bed set in the middle of the room, rhymed with the deer seen at the fairy's home and added to the film's rich bestiary. Already, in this sketch drawn by Demy in his youth, the stags' antlers are mixed up with the trees, blending animal and vegetal like a foreshadowing of Donkey Skin's castle.

At the outset, Demy had naturally called on his collaborator, the production designer Bernard Evein, but the latter renounced for lack of means to realize them. He was replaced by Jim Leon, whom he had met in San Francisco, representing an art that crossed Pop Art and aesthetic conventions of the fairytale in a riot of colours and a profusion of materials. The English painter created 28 set designs that have now disappeared; the screen, an element from the king's hall, and the film's poster attest to this psychedelic trend.

A characteristic peculiar to the fantastic element, the film frees itself from any precise historical reference, and as in Michel Legrand's music, combining harpsichord and electric, styles and epochs coexist: the Princess's Louis XV dresses and the Prince's Henri II costume… Classic elements such as the ruff and vaporous Hollywood-star negligee for the Lilac Fairy… The King's exaggerated puff sleeves whose form and volume take inspiration from compositions by Eisenstein or Welles…

Everything is distributed and composed round a strong idea: one royal family in red and the other in blue. Agostino Pace remembers this chromatic division: « We agreed together that we would paint all the elements, from faces to furniture by way of the horses. »

Demy called on Pace, a stage costume designer, who designed the main characters' costumes, whereas Gitt Magrini – costume designer for Antonioni and Bertolucci – was in charge of conceiving them and having them made in Italy.

« bal des chats et des oiseaux »

The highlight of the show, the Princess's dresses had to defy the imagination, since even the Lilac Fairy did not think « that was possible ». No less than ten dresses were planned, as opposed to « only » four different costumes for the Prince.

The first drawings bring out voluminous puff forms, similar to the King's costume: like father, like daughter. With all the decorative excess necessary: « One must feel the fabrics,' wrote Demy in his preparatory notes. Brocades, sequins, diamonds, veils, crystals, pearls, etc. Simple but bright colours, childish illustrations closer to Disney than to good taste, or more Disney than [Gustave] Doré. »

And although it is a real donkey skin that the fleeing princess wears over her shoulders, the weather-coloured dress was a creation from start to finish, made of the same material as movie screens and thereby the ideal support for any kind of projection… Projection in the film, the dress showing weather and clouds, or the « projections » of the spectator, who did not believe « that was possible » either.

From sketches to costumes

Catherine Deneuve: « The dresses were heavy to wear, and it was difficult to stroll in the interminable staircases of the château de Chambord. But those difficulties did not interest Jacques. For him, it was as if a dancer had come to complain about his bleeding feet or his broken back. It had no relation with the film itself so why talk about it? »

On the one hand: the Princess's dresses, which are pure creation and fantasy; on the other: the famous real dead donkey skin that the Princess puts on to flee… Her costumes summarize this constant tension between magic and realism that is the basis of the film's fantastic element. Pace tells us that he had first proposed « using a fake skin, but Jacques wanted at all costs a real one, so we went to the slaughter house to find one. It was incredibly heavy. And then the odour was horrible! So it was necessary to have it cleaned and treated. » In the end, the skin became the symbol of the film: it was that which was chosen, rather than the dresses, to clothe the princess on the poster of the film, drawn by Jim Leon.

Hector Pascual: I remember the first day when I went to do the fittings with Catherine Deneuve. We had had to have the skin reworked. As was, there would have been living worms because, as I told you, the skin was authentic, so I had to readapt it. When you remove the skin from an animal, it remains « alive », organic. I remember having lined it four or five times. Jacques Demy had told me: « Don't say anything to Catherine! », otherwise, she would have never worn it.

Gaël Lépingle: The dresses were very heavy; was the skin, too?

HP: Yes and no. I invented the way that allowed for the skin to hold easily on her. I had to put a material that looked like flesh, skin, but fictive.

Bertrand Keraël: So what was the inside made of? Fabric?

HP: It was nylon paper, plastic, that I then painted. I had gathered information on the way skin dries out.

GL: It's a strange mixture of fiction and authentic…

HP: And that's why it's quite poetic. Personally, I think that things are never dead. You always have to be in relation with the living. If the fashioning had seemed dead, life would not have been transmitted to the screen.

I consider Catherine Deneuve quite strong: wearing that skin that must have seemed bloody…

dresses reconstruction

A few tricks: Appearances: Donkey Skin in the Prince's room. Disappearances: the lovers' boat that glides over the water and vanishes. Transformations: a rose with a mouth that speaks. Film run backwards: the candles light up by themselves. Slow motion: it serves for going from one world to the other, to creating a time that does not exist in ordinary time. Amongst other charms, the Lilac Fairy multiplies trick pleasures: bothered by the yellow of her dress, she changes the colour immediately (matte shot with the tree trunk); she comes and goes as she pleases, suddenly appearing and disappearing, or resorts to an effect of transparency (sudden or progressive appearance); she masters space, as well as time, and it is the famous anachronism of her return at the end in helicopter…

Unlike a special effect, made later in a laboratory, a process shot according to Demy had to keep an artisanal or « primitive » side, created during the shooting if possible. Sometimes, it was the cinematographic language itself that served as trick and became magical again: the doubling of Donkey Skin into princess in the cabin, by the sole thanks to the angle/reverse angle and hooting script; the carriage that turns back into a « pumpkin » owing to a simple cut-in of one shot to another.

The handwritten list of process shots gives an idea of their importance, their variety... and their simplicity: « appearances/disappearances, transformations, slow-motion (combined with a forward or a backwards action), speeded-up action, magic wand, stopped characters »... Demy, a contemporary of the New Wave and, he too, heir to the realistic cinema of the Lumière brothers, also says what his art owes to Méliès, his phantasmagoria and his « visible transformations. »

The fantastic element in Donkey Skin depends on this balance between magic and realism at the same time that it is nurtured by a legendary story and a whole iconography that preceded it: old engravings, magic lantern plates, silent cinema…

A legend and an imaginary universe that take root in the Romantic tradition of 19th century France.

As if by magic, i.e., with the greatest naturalness, the contemporary influence of the hippie style – which Demy witnessed during his stay in Los Angeles – incorporated itself into this old tradition.

Counterculture and psychedelics light up the dream sequence [in which the lovers want to do what is forbidden and smoke the pipe in hiding, where strange coloured flowers grow in the fields, where open-air banquets make wine flow]. As for the flowered beard of the « red » king, it certainly evokes Charlemagne but, perhaps even more, in the late 1960s, a decidedly hegemonic flower power. And as if to authenticate this link, Jim Morrison in person, lead singer of The Doors, came to visit the set at Chambord, a moment immortalized by Agnès Varda's camera.

Jacques Demy saw The Devil's Envoys (1942) at the age of 11: the vision of a stylized Middle Ages and perception of a poetic realism transposed in a France of troubadours and evil creatures…

But above all, it was Jean Cocteau's Beauty and the Beast that he and Pace watched several times during the preparation of the film: the presence of Jean Marais, the Beast's costume, living décors, tricks, a mysterious path in the forest, a magic formula, the role of mirrors…

Jacques Demy was six when he saw Snow White and the Seven Dwarves. He would remember the glass casket, the song, the cake, the friendly presence of forest animals. For Donkey Skin, Demy also rethought Cinderella, her fairy godmother (and advisor) and the pretty foot gliding into the glass slipper… and Sleeping Beauty.

tribute to Cocteau

As in the mirror or in a reflection, the other is a double, a projection of oneself: the Prince splits himself to enter his dream, just like Donkey Skin to make her cake. But the mirror, as cinema knows since Cocteau, is also a secret passage to another world. And this passage carries out a veritable metamorphosis in everyone. Only then can the tale come to an end, having itself achieved its transformative power that can only be brought about by its reading or viewing (its « projection »). At the very end of the film, the ugly donkey skin slips to the ground and reveals the sun-coloured dress; the Prince grasps the hand of his princess and leads her to his father and mother, or rather, towards the camera, which has taken the place of the parents. Then we are on the terrace at Chambord: Demy links in the movement. The young couple, now seen from behind, finishes its advance. The Prince and Donkey Skin have gone to the other side of the mirror and completed their metamorphosis. Like Alice, the marvellous lovers henceforth know that mirrors are made for being crossed.

The clean and the beautiful will therefore be the measure of all things, and ugliness or filth, a veritable obsessive fear. The Fairy's proposal to cover her goddaughter with the donkey skin becomes a transgression: dressing in a smelly skin, covering one's face with soot, living on a farm run by a shrew who spits out toads… Logically, it is the laundresses, personifications of cleanliness, who begin by mocking Donkey Skin.

Thanks to her magic wand, Donkey Skin will make her cabin a transitory place, a place of her own and quite singular since cleanliness and dirt rub shoulders indiscriminately: luxury and poverty, earthen jars and splendid armchair. The film critic Serge Daney noted that the song of the love cake was like the film's fold: midway through Donkey Skin's journey between the two castles, it makes the Princess and the slattern coexist at that moment.

A donkey defecates gold… The banker-donkey offers the King the product of its bowels, like small children presenting their faeces to their parents as a gift. This is a key for understanding the law that rules the Kingdom: a place where shit is established. The clean and the beautiful will therefore be the measure of all things, and ugliness or filth, a veritable obsessive fear. A weather-coloured dress is inevitably the colour of good weather; Donkey Skin starts housecleaning as soon as she enters her cabin, and the maidens of the realm are ready to do anything to get a ring on their finger: « You have to suffer to be beautiful ». Language itself is contaminated by this imperative of the Beautiful: without meaning to, the Fairy begins speaking in rhymes (« une robe moins commune / une robe couleur de lune ») or in alexandrines (« La vie n’est pas aussi aisée qu’on croit / qu’on soit petites gens ou bien fille de Roi »).

Donkey Skin is a tale for children, but there are hardly any children in the film, and barely more in Jacques Demy's other films. If little ones are as unobtrusive in a universe however allotted to the world of childhood, it is because adults have taken their place. Donkey Skin changes dresses in her cabin as if she were playing with dolls and bakes her love cake as if she were playing merchant. The Prince throws tantrums and sulks, and his face brightens only when he admits his secret dream: « I'd like Donkey Skin to make me a cake. » The Princess and the Prince seem even more to be constantly performing, as if acting out a Christmas pageant for their parents, a comedy of innocence and a song of happiness.

But happiness is only a dream, and childhood is often solitary: « I need calm, I didn't say I needed company, » says the Prince. And his relationship with the Princess is less one of lovers than one of brother and sister in which we again find the spectre of incest. The sublimation of sexual relations, a constant in Demy's work, masks a taboo whose price is melancholy. Demy would end up eliminating these lyrics, doubtless overly explicit: « We shall do what is forbidden / Until exhaustion, until boredom. »

One can be both parent and child: Catherine Deneuve plays the Queen and her daughter. No offspring, but an identical reproduction or « self-begetting ». The only (pro)creation at work in Donkey Skin, the sole successful transformation, is the making of the cake. For although the Princess must turn into a slattern before getting back her royal finery, what did she gain from this ordeal? Whereas every fairytale or fantastic story presents a transformation/emancipation of its character, Demy's film remains ambiguous, and morality is not necessarily intact. It is easy for the Lilac Fairy to forbid incest for « questions of culture and legislature », but there remains a delighted smile on the Princess's face when her father finally finds her again and assures her that, henceforth, « we shall never leave each other again ».

about the tale of Donkey Skin

When the girl in Umbrellas of Cherbourg announces to her mother that she is pregnant, the latter exclaims: « But how is that possible? » The act of love poses problems. Children seem to be born in cabbages or in an eggshell, like this chick that is miraculously born during the making of the cake.

If donkeys defecate gold, how do we find our bearings? From the donkey (âne) to anality, Freudian theory positing that the child imagines himself a newborn « evacuated like an excrement » is not far. Hence the importance of food in Donkey Skin: the sexual act shifts and finds its metaphor in nutrition. The banquet hardly appeals to the Prince who will recover his appetite by devouring his beloved's cake at the risk of suffocating. « We shall stuff ourselves with pastries », they sing together, and since it is the same thing here, « we will have heaps of children. »